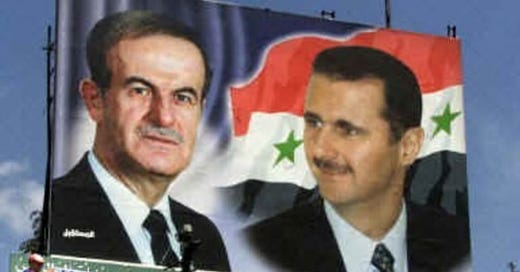

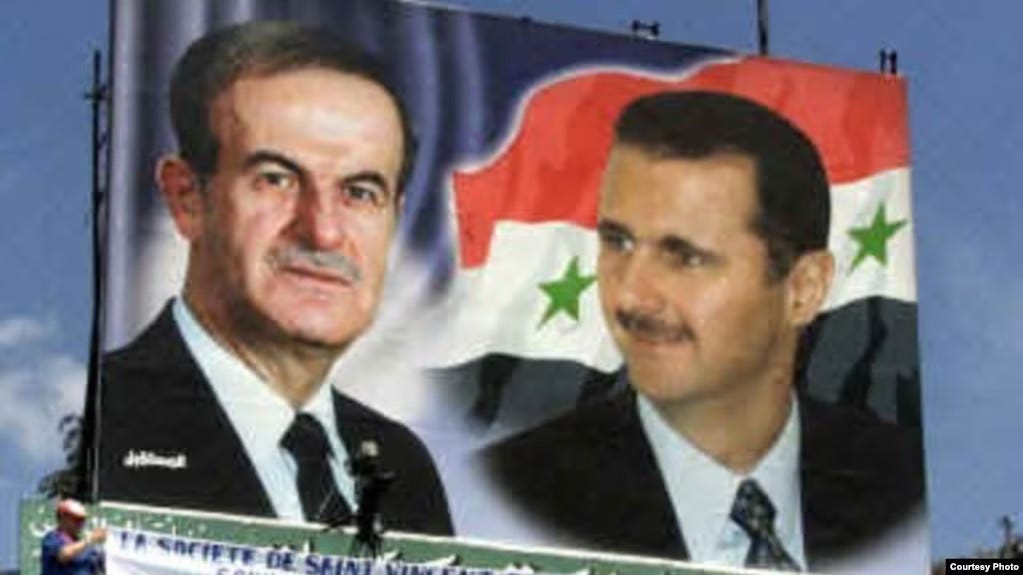

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (right) took over from his father Hafez in 2000.

As the final hours of the al-Assad regime seem to be ticking away, Syria stands at a crossroads where its turbulent past and uncertain future converge. With the dynasty’s grip on power crumbling, now is the time to reflect on how this era came to be—and what might rise from its ashes.

The Coup That Cemented Power

To understand how Syria’s al-Assad dynasty came to rule—and how it may be ending—you have to revisit a 1970 coup orchestrated by Hafez al-Assad. As the Syrian Minister of Defense, Hafez outmaneuvered rivals in the Baath Party, launching what was euphemistically called the "Corrective Movement." It was a bloodless coup, though hardly gentle: Hafez sidelined ideological competitors and consolidated his rule with military precision, creating the authoritarian state that Bashar al-Assad would later inherit.

The rise of Hafez al-Assad mirrors Saddam Hussein's power grab in Iraq in 1979. Both men clawed their way to the top of the Baathist power structure, used brutal purges, and claimed to be defenders of Arab nationalism—all while ensuring personal survival came first.

Bashar’s Unlikely Rise: From Doctor to Despot

Hafez al-Assad’s original successor wasn’t supposed to be Bashar but his elder son, Basil al-Assad. Known as “The Golden Knight,” Basil was a commanding figure, groomed from a young age to inherit Syria’s highest office. His public image combined military prowess with political ambition—traits his father valued deeply. However, in 1994, Basil’s fast-paced lifestyle caught up with him when he died in a high-speed car crash, leaving the Assad dynasty without its chosen heir.

The task of succession fell to the far less prepared Bashar, who at the time was studying ophthalmology in London. He was summoned back to Syria and thrust into military and political training, ascending quickly through the ranks. Though initially presenting himself as a reform-minded modernizer, Bashar soon abandoned any pretense of liberalization. Internet cafes opened briefly, and Western media flirted with optimism—until the regime’s old habits of censorship, surveillance, and repression resurfaced.

Despite his medical background, Bashar ruled with a hardened authoritarian style that echoed his father’s. His unlikely transformation from mild-mannered doctor to dictator highlights both the iron grip of Syria's political machinery and the unavoidable burden of family legacy.

The Alawites: A History of Marginalized Power Players

The al-Assads belong to Syria’s Alawite minority, a Shiite-linked religious group constituting about 12% of the population. The Alawites trace their origins to an offshoot of Twelver Shia Islam but incorporate beliefs distinct from mainstream Islam, blending Islamic teachings with pre-Islamic Gnostic and Neoplatonic influences.

Their spiritual practices are often kept secret, contributing to widespread suspicion from Sunni Muslims, who form the majority in Syria and the broader Islamic world. Alawite theology includes belief in the divine nature of Imam Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad. They celebrate some Islamic holidays but also observe rituals unique to their faith, including the veneration of saints and symbolic religious ceremonies.

Geographically, Alawites are concentrated in Syria’s coastal mountain regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus, where their communities have long been isolated and vulnerable. Smaller Alawite communities also exist in Lebanon, Turkey, and Israel.

In Israel, the Alawite population is centered primarily in the Golan Heights, a disputed region captured from Syria in 1967. The community is small but distinct, having adapted to life under Israeli governance while maintaining strong cultural and religious ties to their Syrian roots. Unlike their Syrian counterparts, who benefited from state power under the al-Assad regime, Israeli Alawites face different social dynamics, balancing loyalty to their heritage with pragmatic coexistence under Israeli rule.

Under French colonial rule in the 1920s, the Alawites were recruited into the military as a means of counterbalancing Syria’s Sunni Arab majority. This decision laid the groundwork for Hafez al-Assad's military ascendancy, culminating in Alawite dominance over Syria's political and military institutions—despite the community's small numbers.

Syria’s Darkest Chapters: Assassinations, Nukes, and International Isolation

Syria’s past is littered with notorious acts, including the 2005 assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, which was linked to Damascus-backed Hezbollah operatives. In 2007, Israeli jets obliterated Syria's covert nuclear reactor in Deir ez-Zor. These events further isolated Syria internationally, though Bashar’s regime weathered them—until the Arab Spring.

The Great Unraveling: A Dynasty Under Siege

Syria's current collapse traces directly to the 2011 Arab Spring, when protests demanding reforms were met with live ammunition. The civil war that followed drew in regional powers, with Iran, Hezbollah, and Russia backing the regime while Turkey and Western allies supported various rebel groups.

Recently, cracks in the regime widened as Hezbollah's forces stretched thin after clashing with Israel in southern Lebanon. Russia, bogged down by its own geopolitical struggles, could no longer sustain its extensive military operations in Syria. Turkey seized this moment of regional instability to bolster its influence by increasing support for Syrian rebel factions.

Ankara has long pursued a dual strategy of opposing the Assad regime while limiting Kurdish territorial gains in Syria. Turkey’s military and intelligence services have strengthened ties with key factions within the Erbil Alliance, funneling supplies, logistical aid, and even air cover in specific offensives. Turkish-backed forces have secured key border regions and exerted influence in northern Syria, helping tilt the battlefield against Assad’s overstretched military.

Amidst this chaos, the Erbil Alliance—a surprising coalition of Islamist factions and Kurdish groups—emerged as a formidable force.

The Rebels: Surprisingly Humanistic Amid the Fog of War

The Erbil Alliance, led by Abu Muhammad al-Julani of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), has confounded expectations. Once linked to Al-Qaeda, HTS formally severed ties in 2016. Under al-Julani, the rebels have reportedly prioritized humanitarian efforts, ensuring safe passage for minority groups like Kurds, Christians, and Yazidis. This measured approach stands in stark contrast to Syria's grim history of sectarian massacres.

What Comes Next? Three Likely Scenarios for Syria’s Future

Fragmentation and a Period of Chaos:

Without a strong central government, Syria could fragment into warring fiefdoms reminiscent of Libya after Gaddafi’s fall. Local warlords and international powers would likely scramble for control, dividing the country into de facto zones of influence. This scenario could create a power vacuum, inviting further foreign intervention from nations like Turkey, Iran, and possibly Russia, despite its current overstretch.Rebel Rule and Stabilization:

If the Erbil Alliance secures Damascus, a fragile coalition government could emerge. However, with such a diverse alliance—ranging from Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and Kurdish militias to secular opposition groups—it’s impossible to predict how power will be distributed. The coalition’s ideological differences could sow internal divisions as various factions compete for control of ministries, resources, and military commands. Disagreements over the roles of religious law, Kurdish autonomy, and relations with foreign powers could paralyze the new government.

This diversity presents both a potential strength and a serious liability. While it could provide broader representation and legitimacy, it might also lead to gridlock or even internal conflict. Historical precedents in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Lebanon suggest that a balance of power among competing factions is difficult to maintain without external arbitration—or brute force.International Trusteeship:

Fearing another failed state, the UN or regional powers could impose an international trusteeship to stabilize Syria. This would involve a transitional government backed by peacekeeping forces, with a mandate to rebuild institutions and oversee elections. However, such an arrangement risks becoming a protracted occupation, as seen in post-war Bosnia and Kosovo. Furthermore, foreign-led governance would likely face resistance from nationalist and Islamist factions within Syria, possibly triggering insurgencies or renewed conflict.

Syria’s future defies easy prediction, as its political landscape is both volatile and deeply fractured. The three scenarios outlined aren’t mutually exclusive—fragmentation and chaos could initially grip the country, only for a fragile coalition to emerge later if the Erbil Alliance consolidates power. While the alliance’s diversity offers a chance for inclusive governance, its ideological and strategic contradictions could spark internal power struggles. The collapse of the al-Assad regime marks the end of an era, but what comes next could shift unpredictably between conflict, compromise, and uneasy stability.

The Current State of Affairs

As of today, reports suggest that Bashar al-Assad’s government is teetering on the brink of collapse. Rebel forces have breached Damascus’s outer defenses, while defecting Syrian Army generals are reportedly negotiating surrender terms. Meanwhile, Iranian advisors have been seen fleeing to the airport, and Russia’s last-ditch airstrikes have failed to halt the advance.

For the al-Assad dynasty, it seems the end has finally come—not with a whimper but with the same ruthless force that defined its rise. As history reminds us, dynasties fall, but the shadows they cast often linger for generations.